- European Central Bank publications

13/ Public sector asset purchases, including of Luxembourg government bonds by BCL, under the PSPP and the PEPP

10 December 2021

Blog post by Gaston Reinesch, Governor of the BCL

In previous blog articles we explained the main conventional and unconventional Eurosystem monetary policy tools from a policy perspective.

This article (with cut-off date on 1 December 2021) starts with a brief overview of the past public sector asset purchase programmes and provides more specific information on the implementation of the ongoing public sector asset purchase programme (PSPP), which represents the largest part of the extended asset purchase programme (APP), and the pandemic emergency purchase programme (PEPP). It also provides a short description of the Luxembourg government bond market and its key characteristics.

The Eurosystem’s very first public sector asset purchase programme started more than a decade ago. In 2010, the sovereign debt crisis hit the European financial markets, which led to rapidly rising government bond yields in a few euro area countries, accompanied by a loss of access to market funding.

In May 2010, the Eurosystem launched the securities markets programme (SMP), which involved secondary market purchases of sovereign bonds of euro area countries under financial stress. The objective of this programme was to address the severe tensions in certain sovereign bond market segments and restore an appropriate monetary policy transmission mechanism.

With a view to ensure that SMP purchases did not affect the monetary policy stance, between May 2010 and June 2014, bond purchases conducted under the SMP were ‘sterilised’ through operations that aimed at re-absorbing the liquidity injected through SMP purchases. Moreover, government bond purchases under the SMP were conditional to certain policy commitments by the corresponding euro area governments to meet their fiscal targets and to ensure the sustainability of their public finances.

As severe tensions in some euro area sovereign bond markets re-emerged, in July 2012, former ECB President Draghi signalled the commitment to preserve the euro whatever it takes. It was finally the announcement of a new public sector asset purchase programme entitled ‘outright monetary transactions’ (OMT), in August 2012, which eased tensions in all euro area sovereign bond markets.[1] In September 2012, the Governing Council announced the termination of the SMP (the liquidity injected through the SMP continued to be absorbed until June 2014).

A necessary condition for OMT is a strict and effective conditionality attached to an appropriate European Financial Stability Facility/European Stability Mechanism (EFSF/ESM) programme in order to avoid moral hazard for governments. Sovereign bond purchases under the OMT, if any, are conducted on the secondary market and focus on the shorter part of the yield curve. In principle, purchases under the OMT are not subject to ex ante quantitative limits. Any liquidity created through OMT is fully sterilised and OMT does not aim at affecting the monetary policy stance.

By early 2015, many indicators of actual and expected inflation in the euro area had moved towards their historical lows. Furthermore, potential second-round effects on wage and price-setting threatened to further weaken the medium-term outlook for price stability. With key ECB interest rates at already very low levels, in January 2015, the Governing Council announced the PSPP with a view to provide additional monetary stimulus.[2] Purchases under the PSPP are conducted on the secondary market and as part of the APP and accounting for the largest part of the pre-announced monthly volume of net purchases under the APP.

The Eurosystem purchases public sector bonds along with private sector securities under the APP at a monthly net pace of € 20 billion. For now, the Governing Council expects net purchases under the APP to run for as long as necessary to reinforce the accommodative impact of its policy rates, and to end shortly before it starts raising the key ECB interest rates.

The PEPP was launched in March 2020 as a temporary, exceptional purchase programme in immediate response to the acute and exceptional economic crisis triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic. The PEPP, which comprises purchases of public sector bonds on the secondary market as well as private sector purchases, has a total envelope of € 1,850 billion[3] and the programme will terminate once the Governing Council concludes that the COVID-19 crisis phase is over, but in any case not before the end of March 2022. The maturing principal payments from these securities will be reinvested until at least the end of 2023.

Public sector asset purchases under the PSPP and the PEPP largely share the same framework, with a few notable differences.

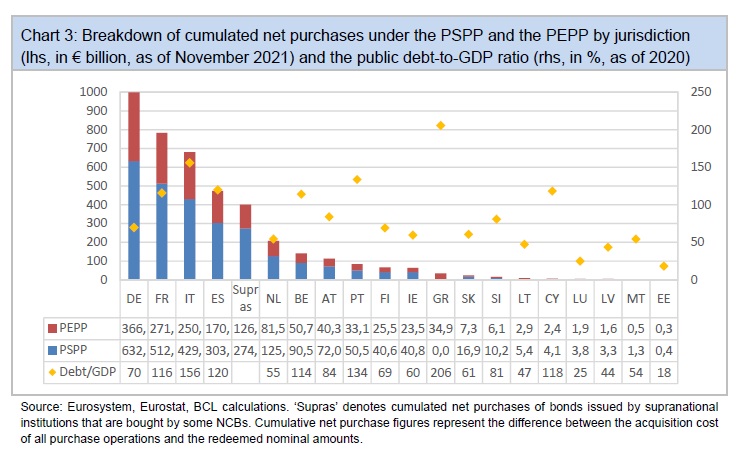

A first common feature is that the allocation of public sector asset purchases among the national central banks (NCBs) is guided by the NCBs’ shares in the ECB’s capital.[4] Every NCB essentially purchases government bonds and bonds issued by recognised agencies of its respective jurisdiction (but not those of other jurisdictions). In other words, these securities acquired by the NCBs are not subject to the Eurosystem’s loss-sharing regime.

Second, some NCBs also purchase securities of euro area supranational institutions on behalf of the Eurosystem as part of the public sector asset purchases, which should constitute in total 10% of all public sector asset purchases.

The third common feature is that the ECB should contribute 10% to the purchases of government securities of all jurisdictions.

Both the NCBs’ purchases of securities issued by supranational institutions and the ECB’s purchases of government securities are loss-shared within the Eurosystem.

What differs in both frameworks relates to the fact that the PEPP is more flexible in terms of purchases and eligibility of certain assets.

First, despite the PEPP’s benchmark allocation for public sector assets according to the capital key, its purchases can still be conducted in a flexible manner to prevent distortions in the euro area sovereign yield curves. For example, in case sovereign bond markets in parts of the euro area were to experience sudden tensions, the Eurosystem could in principle purchase more sovereign securities of that jurisdiction than foreseen by the benchmark with a view to prevent fragmentation and impairments in the monetary transmission process.

Second, Greek government bonds are only eligible under the PEPP due to the granting of a waiver which exempts them for not meeting the minimum rating criterion as stated in Decision (EU) 2015/774.

Furthermore, while the residual maturity of securities eligible for PSPP purchases ranges from 1 year up to 30 years and 364 days, the residual maturity of public sector securities purchased under the PEPP ranges from 70 days up to 30 years and 364 days.

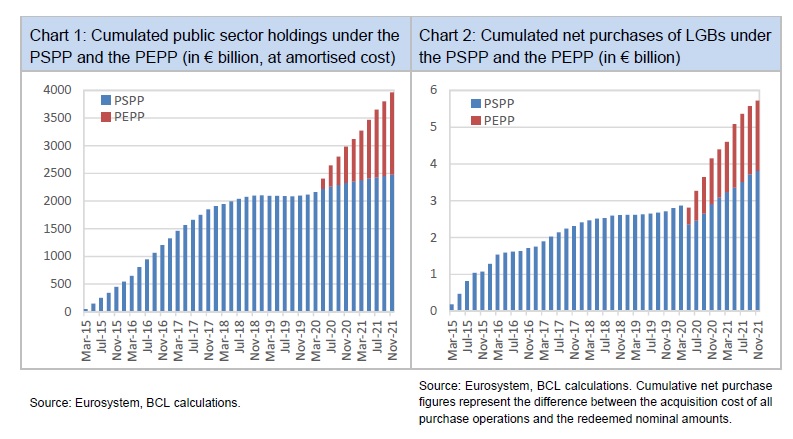

Public sector securities held by the Eurosystem under the PSPP and the PEPP have almost reached € 4,000 billion by November 2021 (see Chart 1), a volume equivalent to a sizeable portion of euro area gross domestic product (approximately € 11,400 billion in 2020). The more rapid increase in holdings under the PEPP in comparison to the PSPP reflects the different monthly pace of purchases of the two programmes.

The Eurosystem’s holdings of Luxembourg government bonds (LGBs) under the PSPP and the PEPP exceeded € 5.7 billion by November 2021 (Chart 2), the large majority of which were purchased directly by the BCL.[5] Hence, a substantial portion of the LGBs currently outstanding (€ 14.25 billion in nominal value) is held notably by the BCL. Such purchases are conducted in the international bond markets and with a large number of institutional counterparties. A key characteristic of the LGB market is its limited size, which is a direct consequence of Luxembourg’s low public debt-to-GDP ratio. The LGB market started to develop only in 2008 with the issuance of a € 2 billion government bond. Since 2008, twelve LGBs have been issued for a total amount of € 18.25 billion and two LGBs for a total amount of € 4 billion have already matured.

Since 2008, the main rating agencies have granted the best credit rating to Luxembourg (Aaa for Moody’s, and AAA for S&P, Fitch). The rating for the Grand Duchy is based on a stable and predictable economic and financial situation, a high level of wealth, and efficient regulatory and institutional structure.[6] Such a creditworthiness attracts a high demand for LGBs as evidenced by investors’ large oversubscription in the primary market at the time of issuance. For example in the case of the LGB 2032, investors have shown a strong interest, with a demand beyond € 12.5 billion, while only an amount of € 1.5 billion has been issued.

Reduced liquidity and limited trading opportunities make the LGB market less attractive for investors who need a market that is always available in order to implement their active investment strategies such as high frequency or arbitrage trading. However, the characteristics of the LGB market fit well with the preferences of medium to long-term investors aiming at holding LGBs for an extended period or even keeping them until maturity (“buy and hold strategy”). Hence, the LGB universe represents a small but high quality government bond market segment characterized by limited liquidity conditions. So far, the implementation of the Eurosystem’s sovereign bond purchases, in principle, has been smooth. That said, the large-scale asset purchases may test sovereign bond market liquidity conditions in jurisdictions benefitting from low public debt.

According to the Securities Holdings Statistics by Sector (SHSS) as of October 2021, LGBs held by domestic and foreign investors amount to EUR 6.24 billion and EUR 8.01 billion (in nominal value), respectively. Apart from the BCL, the vast majority of domestic holders of LGBs are institutional investors which include banks (€ 1,530 million), investment funds (€ 250 million), insurance companies (€ 200 million), while only a small amount of LGBs are held directly by households (€ 25 million).

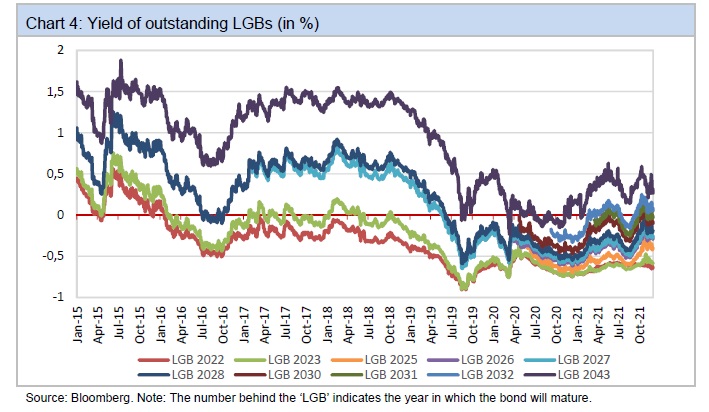

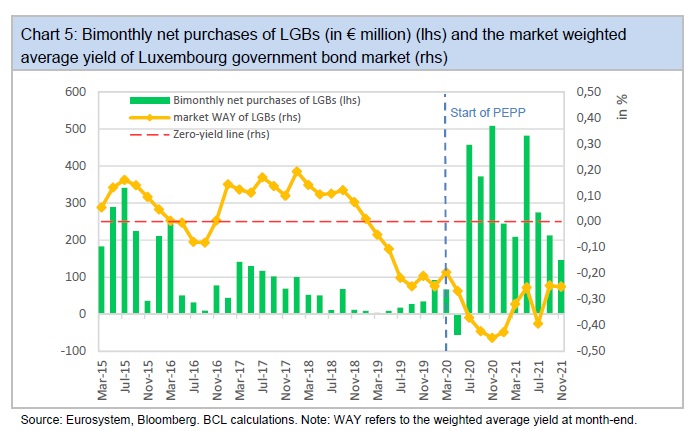

Public sector asset purchases conducted by the NCBs expose central banks’ balance sheet to a risk. In fact, each NCB absorbs, as already mentioned, the total financial losses/gains on the government securities it purchases from its own jurisdiction. Over the past years, government bond yields have steadily declined and those of many euro area countries, including Luxembourg, have turned negative (see Chart 4 for LGB yields). Since the start of the PEPP implementation in March 2020, the BCL has acquired a significant amount of LGBs at negative yields, which led to significant balance sheet costs for the BCL. Chart 5 illustrates the flow of LGB net purchases by the Eurosystem and the average market yield of LGBs weighted by its nominal amount outstanding.

To sum up, the PSPP and the PEPP have proved to be important and effective monetary policy instruments enhancing the transmission of monetary policy, facilitating the provision of credit to the euro area economy, easing borrowing conditions for households and firms, and supporting the convergence of inflation rates to the Governing Council’s now symmetric inflation target of two per cent over the medium term. Furthermore, the Eurosystem’s prompt and voluminous response throughout the pandemic crisis has accelerated the recovery of the euro area economy in general and of the Luxembourg economy in particular. While the purchase programmes supported the monetary policy transmission mechanism, the inflation dynamics and the economic activity in the euro area, the same purchases have also contributed to a significant increase in the central banks’ balance sheet and financial risk exposure. Moreover, large-scale asset purchases may test sovereign bond market liquidity conditions in jurisdictions benefitting from low public debt. Finally, the large volume of sovereign bonds purchased implies that Eurosystem central banks have become an important holder of public debt in the euro area.

Cut-off date: 1 December 2021

______________________________

[1] The announcement of OMT was so effective that as of today no bonds had to be purchased under the OMT.

[2] In December 2014, the inflation rate in the euro area had turned negative and reached -0.6% in January 2015. A package of unconventional monetary policy measures, including private sector asset purchases and targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTROs), had already been announced in the second half of 2014 to reverse the disinflation trend.

[3] In March 2020, the envelope for the PEPP was initially set at € 750 billion. In the course of the year, the Governing Council revised upwards the total envelope of the PEPP purchases by € 600 billion in June 2020 and by € 500 billion in December 2020 to a new total amount of € 1,850 billion. The envelope of € 1,850 billion does not need to be used in full if favourable financing conditions can be maintained. PEPP purchases exceeded € 1,545 billion by November 2021.

[4] The NCBs’ shares in the ECB’s capital are calculated using a key that reflects the respective country’s share in the total population and gross domestic product of the EU. These two determinants have equal weighting.

[5] It can be observed in Chart 2 that the LGB holdings under the PSPP experienced a decline in May 2020, which is explained by the redemption of LGB holdings that matured during that period.

[6] The Luxembourg economy has so far resisted well to the pandemic crisis, due inter alia to the rapid and voluminous response from the Eurosystem and other central banks, which prevented the transformation of the economic crisis caused by the sanitary measures, into a financial crisis. In view of the relative importance of the financial sector in the Luxembourg economy, this reaction, ceteris paribus, shielded the Luxembourg economy from more significant damage.