- European Central Bank publications

23/ Normalising the ECB monetary policy: A data-dependent transition towards a level of policy rates ensuring the timely return of inflation to the two per cent medium-term target

1 March 2023

Blog post by Gaston Reinesch, Governor of the BCL

Normalising the ECB monetary policy: A data-dependent transition towards a level of policy rates ensuring the timely return of inflation to the two per cent medium-term target[1]

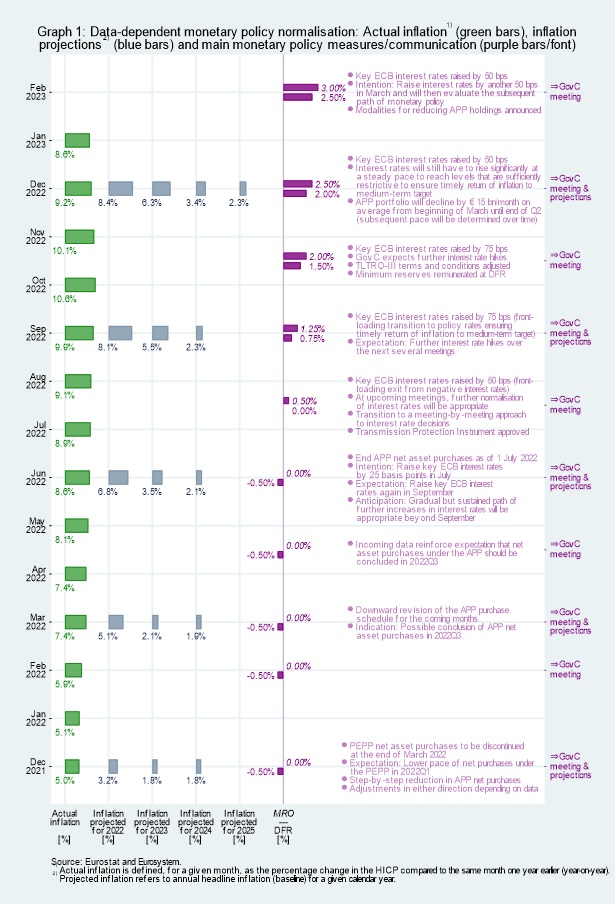

December 2021 – April 2022: Launching monetary policy normalisation

In December 2021 the Governing Council assessed that the progress on economic recovery and towards its medium-term inflation target permitted a step-by-step reduction in the pace of its asset purchases.[2] Among other measures, the Governing Council announced the discontinuation of net asset purchases under the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) at the end of March 2022.

Throughout 2022, the Governing Council reassessed the euro area inflation outlook taking into account latest incoming data and developments as well as macroeconomic projections. With inflation pressures intensifying, in March 2022, the Governing Council indicated a possible conclusion of net asset purchases under the Asset Purchase Programme (APP) in 2022Q3.[3]

June 2022 – July 2022: Frontloading the exit from negative interest rates and from highly accommodative levels of policy rates

For most of the first half of 2022, price pressures were by and large limited to the HICP’s energy and food items - mainly owing to Russia’s unjustified war against Ukraine and its people - and the rise in inflation was expected to be relatively short-lived.[4] By June 2022, that outlook, however, had changed significantly.

First, the June 2022 Eurosystem staff baseline projections entailed a significant upward revision to the inflation path going forward. Energy costs had pushed up prices across many sectors. Supply shortages and the normalisation of demand as the economy reopened added to price pressures. Food prices had increased sharply, reflecting elevated transportation and production costs, partly related to the war in Ukraine. Wage growth had started to pick up.[5] While various measures of longer-term inflation expectations stood at around two per cent, initial signs of above-target revisions in such measures warranted close monitoring.[6]

Second, the June 2022 baseline projection suggested that inflation would remain undesirably elevated for some time, exceeding the medium-term inflation target for all three projection years (i.e. 2022 – 2024). Owing to the broadening of price pressures, inflation excluding the more volatile energy and food components[7] – so-called “core inflation” covering approximately 70% of the euro area HICP – was projected to remain above 2 per cent for three consecutive calendar years.

On the basis of its updated assessment of the inflation outlook, in June 2022 and July 2022 the Governing Council took further steps in normalising monetary policy, such as ending net purchases under the APP as of 1 July 2022. In July, the Governing Council raised the key ECB interest rates by 50 basis points, bringing the interest rate applied to the Eurosystem’s deposit facility to zero per cent.[8] Pointing to a further normalisation of interest rates at upcoming Governing Council meetings, in July the Governing Council also announced a transition to a meeting-by-meeting approach to interest rate decisions.[9]

September 2022 - February 2023: Towards policy rate levels sufficiently restrictive to ensure a timely return of inflation to the two per cent medium-term target

By September 2022, euro area inflation had increased to 9.9 per cent. While inflation still rose mainly because of surging energy and food prices, persistent supply bottlenecks for industrial goods and recovering demand, especially in the services sector, as well as the depreciation of the euro also contributed to high inflation.

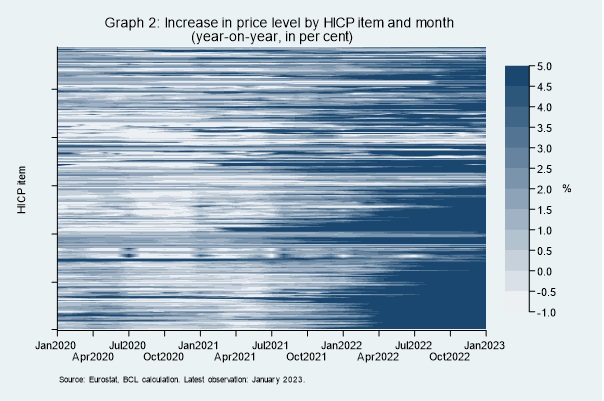

With price pressures broadening further, in September, prices of approximately 15 per cent of all HICP sub-items published by Eurostat had increased by less than two per cent year-on-year (down from roughly 85 per cent two years earlier, see graph 2 below). At the same time, prices of approximately 55 per cent of HICP sub-items increased by more than 5 per cent year-on-year (up from roughly 4 per cent two years earlier). Inflation excluding energy and food had increased to 4.8 per cent (up from 1.9 per cent in September 2021), the highest rate since the introduction of the euro back then.

The September 2022 ECB staff projections brought additional upward revisions to the projected inflation path and the Governing Council assessed that the risks to the inflation outlook continued to be primarily on the upside.

Against this background, in September, the Governing Council raised the key ECB interest rates by 75 basis points. This major step, representing the largest interest rate increase implemented by the Governing Council hitherto, permitted to frontload the transition from highly accommodative policy interest rates towards levels that would ensure a timely return of inflation to the 2 per cent medium-term target. The Governing Council also announced it expected to raise interest rates further over the next several meetings to dampen demand and guard against the risk of a persistent upward shift in inflation expectations. [10]

In October, year-on-year inflation had reached the highest reading for the euro area recorded so far (10.6 per cent). With inflation remaining far too high and likely to stay above target for an extended period, the Governing Council raised key ECB interest rates again by 75 basis points. With this third consecutive major policy rate increase, the Governing Council made substantial progress in withdrawing monetary policy accommodation. The Governing Council also reiterated again its expectation to raise interest rates further to ensure a timely return of inflation to the two per cent medium-term inflation target.[11]

While year-on-year headline inflation declined from 10.6 per cent in October to 9.2 per cent in December, price pressures remained strong. Inflation excluding energy and food increased further to 5.2 per cent, the highest level since the introduction of the euro back then.

By December, supply bottlenecks had eased and the effects of the pandemic-related restrictions being lifted had weakened, but they still contributed to inflation. The depreciation of the euro continued to feed through to consumer prices.[12] Wage growth continued to be supported by robust labour markets and some catch-up in wages to compensate workers for high inflation. While most measures of longer-term inflation expectations stood at around two per cent, above-target revisions to some indicators warranted continued monitoring.[13]

The latest December 2022 Eurosystem staff baseline projections suggested another substantial upward revision to the inflation outlook. Inflation was projected to reach 8.4 per cent in 2022 before declining to 6.3 per cent in 2023, to 3.4 per cent in 2024 and to 2.3 per cent in 2025.[14] Inflation excluding energy and food was projected to be 3.9 per cent on average in 2022 and to rise to 4.2 per cent in 2023, before declining to 2.8 per cent in 2024 and 2.4 per cent in 2025.[15]

Even though the horizon of the December projections for the first time extended to 2025, neither headline nor core inflation were expected to return to two per cent on average by the final year of the projection under the baseline scenario.

In December, the Governing Council also continued to emphasise the extraordinary degree of uncertainty underlying the staff projections (and other projections and forecasts) and the headwinds weighing on economic activity in the euro area and the rest of the world, especially owing to Russia’s unjustified war against Ukraine and its people.

While throughout 2022 the Eurosystem and ECB staff baseline projections implied significant upward revisions to inflation, they also saw downward revisions to growth for 2023.[16] Euro area activity slowed down considerably as the rebound in services owing to the reopening of the economy weakened, global demand softened, the terms of trade deteriorated and high inflation weighed on consumption and investment.

At the same time, the euro area economy held up better than previously expected.[17] The December 2022 projections concluded that the euro area economy may contract around the turn of the year, but a recession would be relatively short-lived and shallow.[18] In the course of 2023, growth was projected to recover under the baseline scenario. Moreover, the December projections suggested, some of the uncertainty could translate into inflation rates yet higher than projected in the baseline.[19]

Throughout (and prior to) the normalisation process, the so-called neutral rate of interest could not be considered a practicable benchmark for monetary policy decisions. While having some appeal on conceptual grounds[20], the neutral rate of interest is neither indirectly nor directly observable and estimates of the neutral rate of interest are notoriously uncertain (even more so in the presence of the shocks and structural change the global economy witnessed in recent years).

An alternative indicator of the orientation of interest rate policy is the level of interest rates that is required to deliver the inflation target (referred to as target-consistent terminal rate in, inter alia, academic research). But the level of policy rates that is consistent with the inflation target is not directly observable either, evolves over time and is highly uncertain. It is conditional on the state of the economy as well as its outlook and contingent on the conduct of monetary policy (e.g. the volume of assets held for monetary policy purposes and the speed of reaching the target-consistent rate) and existing data.

The Governing Council therefore continues to reassess meeting-by-meeting on the basis of incoming data and in line with the evolving outlook the path of interest rates required to reach the two per cent medium-term target and to decide on whether to raise key interest rates further and, if so, by how much.

In the context of the meeting-by-meeting reassessments the Governing Council takes into account structural factors that may affect the long-term equilibrium real interest rate, but also cyclical factors which may call for policy rates corresponding to levels above or below the long-run equilibrium interest rate in order to stabilise inflation at target in the medium term.

Against this background, in December 2022, facing the prospect of inflation remaining far too high and staying above target for too long, the Governing Council again raised the three key ECB interest rates by 50 basis points. Moreover, the Governing Council also judged that while much progress had been made on the normalisation path, interest rates would still have to rise significantly at a steady pace to reach levels sufficiently restrictive and to keep them at restrictive levels to reduce inflation over time and to ensure a timely return of inflation to the two per cent medium-term target.

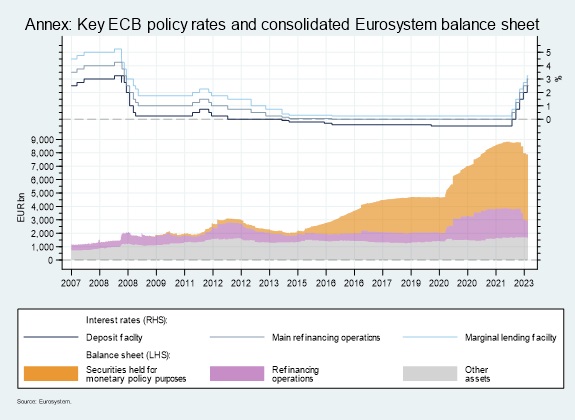

While the key ECB interest rates are the primary tool for setting the monetary policy stance, they are not the only tool. With a view to align all its instruments with the ongoing normalisation process, in December, the Governing Council announced the principles for normalising the Eurosystem’s holdings under the APP.[21]

Among other elements, the Governing Council announced that from the beginning of March 2023 onwards, the Eurosystem would no longer reinvest in full the principal payments from maturing securities purchased under the APP. Instead, the APP holdings would decline at a measured and predictable pace, namely by EUR 15 billion per month on average until the end of the second quarter of 2023, an amount smaller than the pace implied by an entirely passive roll-off of the APP portfolio in line with securities maturing. The measured decline in the APP holdings will contribute to the ongoing normalisation of the Eurosystem’s balance sheet (see also the graph in the annex to this article). Beyond the second quarter, the Governing Council announced, the pace of reduction would be determined over time.[22]

In January 2023, the inflation rate declined further to 8.6 per cent year-on-year, mainly owing to a swift reduction in energy prices. After the release of the December 2022 projections, wholesale gas prices and some commodity prices declined substantially to levels well below the technical assumptions underlying the baseline projection.

The current inflation dynamics, but also the future inflation profile much depend on the type, the timing and the amount of fiscal measures aiming to compensate households for high energy prices and inflation (e.g. gas price caps). These measures are set to dampen inflation now and in the short-term, but ceteris paribus will mechanically result in higher headline inflation once they are withdrawn (in 2024 in particular).

One cannot exclude the drop in energy prices to lead to a headline inflation profile lower than the one suggested by the December baseline. The very large increases in energy prices in early 2022 will give rise to a substantial downward base effect on energy inflation in the coming months. That said, it is very uncertain whether energy prices remain at their present relatively low levels. Furthermore, even if the decline in energy prices were to last, the speed as well as the strength of the pass-through from wholesale energy prices to retail prices and headline inflation remains uncertain too. In addition, if energy prices were indeed to stay at levels lower than those assumed in the context of the December projections, the near term inflation-dampening impact of fiscal measures compensating for high energy prices would be smaller than expected too.

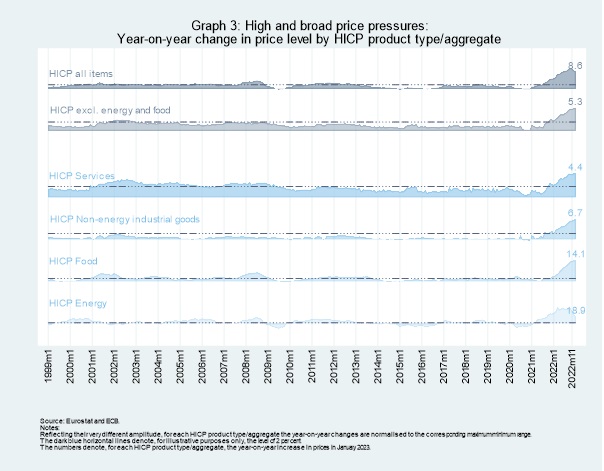

Moreover, compared to the Governing Council’s medium-term target and from a longer-term perspective, price pressures remain exceptionally high for non-energy items. In January 2023, prices of energy, food items, non-energy industrial goods and services increased year-on-year by 18.9 per cent, 14.1 per cent, 6.7 per cent and 4.4 per cent, respectively. For all major HICP product types (save energy), in January 2023, the year-on-year increase in prices stood at the highest level recorded since the introduction of the euro (see graph 3 below).

Following its December judgement that interest rates would have to rise significantly at a steady pace to reach levels that are sufficiently restrictive to ensure a timely return of inflation to its medium-term target, in February, the Governing Council stayed course by again raising all three ECB key interest rates by 50 basis points.[23]

Key interest rates are currently 300 basis points up from their lowest levels (which prevailed since September 2019 in the case of the deposit facility rate and since March 2016 for the interest rates applied to main refinancing operations and the marginal lending facility).[24]

Unlike headline inflation, some measures of underlying inflation continued to rise in January 2023. Year-on-year HICP inflation excluding energy increased slightly to 7.3 per cent in January 2023, the highest level since the introduction of the euro. Year-on-year HICP inflation excluding energy and food increased slightly to 5.3 per cent, a euro area record high. In January 2023, the year-on-year change in the ECB’s Supercore measure had further increased slightly to 6.2 per cent, the highest rate reported since the start of the series in 2003.

In view of the underlying inflation pressures the Governing Council intends to raise interest rates by another 50 basis points in March and will then evaluate the subsequent monetary policy path.

It is true that energy prices have dropped significantly and feed into lower headline inflation. On their own, however, substantially lower energy prices are currently no reliable indicator when assessing the medium-term outlook for price stability. Reflecting a partial reversal of the supply-side shock the euro area faced in 2022 as well as base effects going forward, energy price developments blur the signal of headline inflation for the medium-term inflation outlook in the coming months.

And while the momentum of price pressures has weakened more recently also for non-energy items[25], it stands to reason that consumer prices continue to rise fast and that inflation remains far above the medium-term target (for some time). Between September 2022 and January 2023, the share of HICP sub-items with prices increasing by less than two per cent year-on-year declined further to approximately 10 per cent (graph 2). Over the same period, the share of HICP sub-items with prices rising by more than five per cent year-on-year increased further to above 60 per cent.

Measures of underlying inflation are of particular importance in periods of substantial supply-side shocks and significant base effects. Once these shocks and effects unwind, headline inflation should adjust to levels determined by underlying inflation pressures[26], which are mainly determined by wage and profit developments which, in turn, depend – among others – on inflation expectations.

Depending on the medium-term inflation outlook, it cannot be excluded at all that more ground may need to be covered after the Governing Council monetary policy meeting in March with a view to reduce inflation over time and to guard against the risk of an upward shift in inflation expectations. Any further steps, whether in continuation of the current pace or at a different pace, will be taken accounting for - among others - the March 2023 ECB staff projections and an assessment of the dynamics of underlying inflation and will be motivated by the firm determination to reach the medium-term inflation target in a timely manner.

[1] I would like to thank Patrick Lünnemann for support in preparing this article.

[2] The Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union establishes price stability as the primary objective of the single monetary policy. In 1998, the Governing Council defined price stability in terms of the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP). Following its strategy reviews in 2003 and 2021, the Governing Council concluded that the headline HICP remained the appropriate measure for assessing the achievement of price stability. When concluding its strategy review in July 2021, the Governing Council considered that price stability was best maintained by aiming for two per cent inflation over the medium term.

Following an average inflation rate of 0.3 per cent in 2020, the December 2021 Eurosystem staff baseline projection saw inflation exceeding the medium-term target in 2021 (2.6 per cent) and 2022 (3.2 per cent) before declining to 1.8 per cent in 2023 and 2024.

[3] See also the blogs “The March 2022 ECB Governing Council monetary policy decisions: Reassessing the inflation outlook and recalibrating monetary policy normalisation” and “The April 2022 ECB Governing Council monetary policy decisions: incoming data reinforcing expectations of monetary policy normalisation”.

[4] The December 2021 and March 2022 staff projections saw headline inflation temporarily exceeding the Governing Council’s medium-term two per cent inflation target, but declining to levels below (December 2021 projections) or slightly above (March 2022 projections) two per cent in 2023 (see blue bars in graph 1).

[5] In 2022Q1 and 2022Q2, year-on-year growth in negotiated wages, for instance, stood at 2.9 and 2.5 per cent, respectively (up from a range between 1.3 and 1.8 per cent reported for 2021).

[6] Between January 2022 and July 2022, for instance, respondents to the ECB’s Survey of Professional Forecasters revised up their longer-term inflation expectations from 2.0 to 2.2 per cent on average.

[7] Following its strategy review in 2021, the ECB Governing Council concluded that the headline HICP remains the appropriate measure for assessing the achievement of price stability. To the extent that very volatile price developments in some HICP sub-items blur the medium-term outlook for price stability, so-called underlying inflation can provide supplementary information about the more persistent component of headline inflation or the level of headline inflation after temporary factors unwind. Measures of underlying inflation can be an important input when assessing the medium-term outlook for price stability, in particular when headline inflation is subject to noise from temporary or idiosyncratic factors and differs substantially from the more persistent price pressures. Next to headline inflation, the Monetary Policy Statement therefore regularly refers to HICP inflation excluding energy and food, which also excludes alcohol and tobacco. Other measures of underlying inflation are, for instance, HICP inflation excluding energy, HICP inflation excluding unprocessed food and the ECB’s Supercore measure of inflation. The Supercore measure is based only on those items of HICP inflation excluding energy and food that are deemed sensitive to slack, as measured by the output gap (ECB Economic Bulletin 4/2018).

[8] The deposit facility rate is the interest rate at which eligible monetary policy counterparties may make overnight deposits at a Eurosystem national central bank. In the current environment of large excess reserves, the level of short-term interest rates (indicative of the initial stage of the monetary transmission process) in the euro area is determined by the level of the Eurosystem’s deposit facility rate. Since June 2014, this rate had been negative. While the focus of the interest rate policy is therefore currently on the deposit facility rate, all five decisions taken since July 2022 to raise that rate entailed a parallel upward move of the other two key policy rates (i.e. the interest rates applied to the main refinancing operations and the marginal lending facility).

[9] As a complement to its rate decisions, in July 2022 the Governing Council also approved the Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI). The TPI ensures that the monetary policy stance is transmitted smoothly across all euro area countries. By safeguarding the transmission mechanism, the TPI allows the Governing Council to more effectively deliver on its price stability mandate. The TPI can be activated to counter unwarranted, disorderly market dynamics that pose a serious threat to the transmission of monetary policy across the euro area. The scale of TPI purchases depends on the severity of the risks facing policy transmission. Purchases are not restricted ex ante. For more details on the TPI, please refer to the dedicated press release. That said, flexibility in reinvestments of redemptions coming due in the PEPP portfolio remains the first line of defence to counter risks to the transmission mechanism related to the pandemic.

[10] Moreover, with the deposit facility rate above zero per cent, in September 2022, the Governing Council suspended the two-tier system for the remuneration of excess reserves introduced in September 2019. Under the two-tier system part of the credit institutions’ current account holdings in excess of minimum reserve requirements were exempt from remuneration at the negative deposit facility rate. The aim of the two-tier system was to support the bank-based transmission of monetary policy while preserving the positive contribution of negative interest rates to the accommodative stance of monetary policy and to the sustained convergence of too low inflation to the two per cent target.

[11] In October, the Governing Council also decided to change the terms and conditions of the third series of targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTROs-III) from 23 November 2022 and to offer banks additional voluntary early repayment dates. The recalibration imposed by monetary policy considerations ensured that TLTROs-III – which played a key role in countering downside risks to price stability during the acute phase of the pandemic – are consistent with the broader monetary policy normalisation process and reinforce the transmission of the policy rate increases to bank lending conditions against the background of the unexpected and extraordinary rise in inflation.

Finally, in order to align the remuneration of minimum reserves held by credit institutions with the Eurosystem more closely with money market conditions, in October the Governing Council decided to set the remuneration of minimum reserves at the ECB’s deposit facility rate (previously at the rate applied to the main refinancing operations).

[12] Between December 2020 and August 2022 the euro nominal effective exchange rate against the currencies of 41 of the euro area’s most important trading partners weakened by 7.2 per cent. This reflected, among others, a depreciation of the euro against the US dollar by 16.8 per cent. While changes in the exchange rate can directly affect the cost/prices of imports and exports, their pass-through to domestic consumer prices is subject to lags. Between August 2022 and January 2023, the euro nominal effective exchange rate against a broad group of 41 partner countries appreciated by 5 per cent, ceteris paribus mitigating price pressures over time.

[13] According to the 2022Q4 ECB Survey of Professional Forecasters - conducted between 30 September and 6 October 2022 - average longer-term inflation expectations remained unchanged at 2.2 per cent.

[14] The September 2022 baseline projections saw inflation at 8.1 per cent, 5.5 per cent and 2.3 per cent in 2022, 2023 and 2024, respectively.

[15] In September 2022, staff baseline projections saw inflation excluding energy and food at 3.9 per cent, 3.4 per cent and 2.3 per cent in 2022, 2023 and 2024, respectively.

[16] The December 2022 baseline projections saw 0.5 per cent growth in 2023, down from 0.9 per cent in September 2022, 2.1 per cent in June 2022 and 2.8 per cent in March 2022.

[17] The December 2022 baseline projections saw 3.4 per cent growth in 2022, up from 3.1 per cent in September 2022 and 2.8 per cent in June 2022. In March 2022, when the baseline included only an initial assessment of the impact of Russia’s war against Ukraine, growth projections for 2022 stood at 3.7 per cent.

[18] The latest Eurostat flash estimate points to slightly positive growth in 2022Q4 (i.e. 0.1 per cent quarter-on-quarter). While euro area growth in late 2022 was affected by the very high growth rates reported for Ireland (3.5 per cent quarter-on-quarter), the outcome was better than expected in December 2022.

[19] With a view to capture some of the very elevated uncertainty surrounding the growth and inflation outlook, the June 2022, September 2022 and December 2022 staff projections featured a downside scenario which included, among others, a complete cut of Russian gas exports to the euro area. As documented by these scenarios, a long-lasting war in Ukraine remains a significant risk to growth. At the same time they suggested that euro area inflation could turn out higher than expected in the baseline (save for the final year of the projection horizon in the case of the June and December projections).

[20] The neutral rate of interest corresponds to the level of the real short-term interest rate that defines a neutral monetary policy stance, a situation in which economic activity is at potential and inflation is at its target level and absent any need to strengthen or withdraw monetary stimulus. The neutral rate of interest is determined by various factors, such as productivity, population growth, time preference, risk premia, fiscal policy and the structure of financial markets (see, for instance, https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/other/pp57-69_mb200405en.pdf).

[21] The Eurosystem started to purchase securities under the APP in October 2014, moment when the deposit facility rate stood at -0.20 per cent and shortly before year-on-year HICP inflation turned negative. Facing the prospect of too low inflation, the APP aimed at supporting the monetary policy transmission mechanism and providing the amount of policy accommodation needed to ensure price stability.

[22] The Governing Council also announced that it would regularly reassess the pace of the APP portfolio reduction to ensure it remains consistent with the overall monetary policy strategy and stance, to preserve market functioning, and to maintain firm control over short-term money market conditions. By the end of 2023, the Governing Council will also review the Eurosystem’s operational framework for steering short-term interest rates, which will provide information regarding the endpoint of the balance sheet normalisation process.

[23] On 2 February 2023, the Governing Council also announced the modalities for reducing the Eurosystem’s APP holdings starting in the beginning of March (see press release). Partial reinvestments will be conducted broadly in line with current practice of reinvestments and include, without prejudice to the price stability mandate, a stronger tilting of corporate bond purchases towards issuers with better climate performance. End-January, the Eurosystem’s holdings under the APP stood at almost EUR 3.300 bn.

[24] Importantly, the swift rise in nominal short-term interest rates is not necessarily reflected in the level of real interest rates linked more closely to consumer and investment spending. The very exceptional price pressures observed in much of 2022 significantly affected shorter-term inflation expectations, thereby attenuating somewhat the rise in short-term interest rates in real terms.

[25] The annualised 3-month on 3-month increase in the seasonally adjusted HICP declined from 10.7 per cent in November 2022 to 5.5 per cent in January 2023. For the HICP excluding energy, the corresponding rate of change declined from 8.3 per cent to 7.1 per cent.